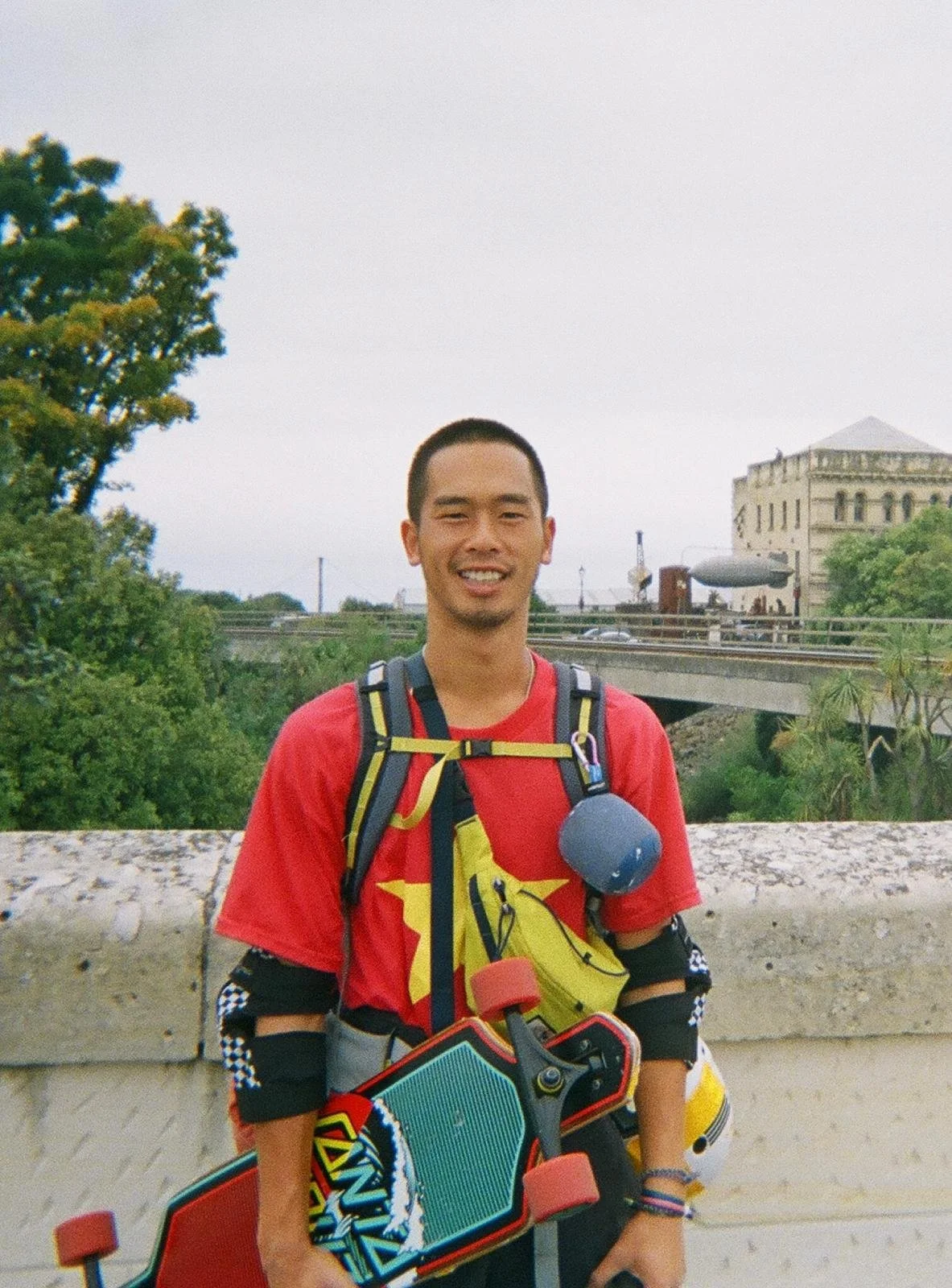

Three countries, a few thousand kilometres, one skateboard and a goofy stance

“The board keeps me fast but keeps me present. And while I’m skating, I want to see if I can do good things along the way.”

Over the past three years, John Addicks O’Toole - Jonny - has clocked up more than 3000 kilometres on his skateboard.

Jonny first found his balance on a skateboard while living in New Zealand’s far north. He was working in a Mangawhai pizzeria with a surf /skate shop next door.

At that time in his life, he wanted to pursue his passion for adventure and pair this with making a positive impact. An idea formed; why not longboard the length of Aotearoa and work with a non-profit group to fundraise? It would be the perfect test project.

To give himself, a beginner skateboarder, the best chance of success, Jonny says he prepared furiously. He studied road seal types, plotted out elevations and the size of road shoulders. He mapped the best routes.

“If skating was going to be the hard part, I wanted to make sure everything else was already accounted for,” he says.

“After that, I thought, ‘Man, maybe this is possible,’ I knew I’d give it my all - and if I had to, I’d tortoise it and take it so slow.”

In early March 2022, Jonny set out on what would become an almost three-month journey across the country. Pushing him along was his mission to raise money for the nonprofit Catalyst Foundation. This organisation fights human trafficking in rural Vietnam, as well as providing mental health support for Asian adoptees in the United States.

Born near Phan Thiết, Vietnam, Jonny was adopted by a family in the US where he grew up in Minnesota.

Finding his birth family when he was 16, he says, they were living in a house that was basically falling apart.

“I had seen all these people on social media doing things all the time where they could run from here to there, walk from here to there, and like raise money for something,” he says. Jonny decided that with the Catalyst Foundation, he would build his birth family a new house.

He started his skate in Bluff, riding on a 36-inch cruiser board. The Santa Cruz Wave Dot Splice was a simple store-bought setup. “I just started,” he says. “I didn’t even really practice.”

With each push, he’d squat slightly on his right foot and push off with his left, riding in goofy stance.

Upon making it all the way to Auckland, a longboarding group told him he was crazy for riding on ‘the terrible wheels and the terrible board for NZ’s road conditions.’

“I didn’t even know,” Jonny laughs. The group gifted him some new wheels that would race him up to Cape Reinga.

NZ’s partiality for a road seal targeted at forestry trucks meant he’d be vibrating his way along as he skated anywhere from 30 to 60 kilometres a day. Wind generated by passing trucks sucked him in the same direction, and he had to learn to ride those currents.

Jonny even skated up hills. He has a theory: there’s a maximum angle that every long-distance skater can efficiently skate up, which is higher than you’d think. But at around 45 degrees, it’s more efficient to walk, he explains.

“So there was a lot of walking in New Zealand,” he says. “I’d be walking up a mountain pass for two hours and then I’d bomb down the other side in 15 minutes.”

Along some especially steep mountain roads and impassable highway sections, Jonny would hitchhike. During these parts, he’d ask a simple question to whoever picked him up: “What do you want to do before you die?”

On this side mission, which he called ‘Roadside Dreams,’ people would weigh up his question quite heavily. A young woman named Love said she wanted her parents to know she was okay dying before them, so they could remember her with light and smiles. Jonny suspected she had a terminal illness.

By the end of Jonny’s skate, he’d raised $36,000, which was enough to build his mum a house and send most children in his village to school for a year. His own dream before he dies - complete.

Wanting to keep up the momentum, Jonny paired with a different non-profit and headed to Cuba a year later in 2023.

It is always within this planning stage that he doubted his adventures. “Why am I doing this? Will I be able to do this? How the heck did I do this last time?” he’d think.

But the moment he’s on his board, Jonny says he just lights up and gets this feeling: “after all the preparation and self-doubt, I’m definitely going to do this.”

It’s not as efficient as biking, Jonny explains. “I put in a lot more effort for those kilometres versus a bike, but can still cruise off on wheels, and I find this challenging and fun - it keeps me honest.”

He thinks of the activity, not as skateboarding but as through-skating. Skateboarding is the time he spent trying again and again and again to pop his board off the ground for the first time; repetition and commitment.

“When I think of through-skating, I think of pacing and efficiency, food intake and water, endurance and safety,” he says. He wouldn’t bomb downhills at usual speeds; instead, he’s more conscious of his backpack and the fact he’s skating them blind - for the first time.

While in Cuba, a rollerblader named Victor toured him around Cienfuegos on wheels. Together with some other friends, they jumped into the sea. At the day’s end, Victor ripped his favourite sticker off his skates and stuck it on Jonny’s board. He didn’t speak much English.

“In my through-skating, I’ve learned that there are people out there in the world who are complex and different to you in ways you could never imagine - and it’s wonderful.”

As a “somewhat portable” part of his kit, he can carry his board through crowded markets and down staircases, held by his side or strapped to his bag. “It feels more like an extension of myself,” Jonny says. “This allows me to flow through many different environments more easily.”

He says he’s never wanted to give up when through-skating, but sometimes he’s been forced to consider whether or not he could actually continue. In Cuba, he puked several times from heat stroke, skating through 30-plus-degree heat. “Safety and injury prevention are some of the biggest factors to consider on these long-distance skates,” he says. New Zealand drivers were the worst. Cuba had potholes and stray dogs.

Aotearoa and Cuba were also solo journeys for the self-proclaimed ‘loner at heart.’ “There is a hyperaware, meditative and self-reliant tone to the trips when solo,” Jonny says. But in Taiwan, where he journeyed in February this year, his friend Troy joined, biking alongside him.

Oozing energy and positivity from his extraverted nature, Jonny says Troy challenged him to interact with others, more than he would normally have done when biking solo. “I valued that a lot,” he says.

Taiwan also differed from his Aotearoa and Cuba trips, where he had generated a huge social media presence to help with his fundraising. As he skated south, Troy cycling along, Jonny refrained from making content and sharing reels of his day. “I didn’t tell anybody,” he says.

"I think a lot and deeply and maybe too much, and I don’t think I was meant to be an influencer. It had become draining on my mental health and took away from the authenticity of my experience in the country as I instead poured my energy into creating this social media image of myself and what I was doing.”

“It’s hard for me to generalise social media as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for the magic of travel,” he continues. Jonny still loves sharing his adventures with whānau.

“But on reflection, I would just urge people to stay true to the moment you’re in and the people you’re in it with, stay humble with the privilege you’ve been given to be able to see the world, and remember: you are not who you are online and validation only matters from yourself and your whanau.”

Starting in Laomei, the northernmost point in Taiwan, Jonny and Troy rolled down the entire west coast, ending in Ul’anbi, the southernmost point. They would stealth camp along the way. “That was probably more scary than the actual skating for me - we were camping under bridges and you’re not sure if someone is gonna kick you out or try to steal your stuff,” he says.

He had plotted the route out and was excited to explore a country he had only read about in history books. “I set myself up to be able to contextualise it as I went through,” he says. “This is a big one for me, as I think a lot of the time, people travel, we see all of these pretty temples and exotic sights, but know nothing about them.”

On this trip, though, he knew something, a fun fact, about every place they stopped. “I feel like learning language, culture, and history is a way that you can show your respect to the places you’re going to,” he encourages.

Taiwan was a trip just for himself. Where he could find again the thrill of exploring and personal freedom which comes with travel. Speaking Mandarin meant he could communicate more deeply with the people he met along the way, as he pushed an average of 50 kilometres each day.

Occasionally, the guys would stay with local Taiwanese hosts. One Hsinchu family was where I (the writer) heard about this crazy-cool guy who was skateboarding through Taiwan. I was cycling and couldn’t imagine how he’d dealt with the hilly terrain I’d been puffing up.

One of the family’s kids enthusiastically showed me the kendama that Jonny and Troy had taught him how to use. I tried too (and failed most of the time). The duo had passed through a week or so ahead of me. I managed to contact Jonny at the end of my own Taiwan cycling trip. Humble and not eager to make a big fuss, he shared his Taiwan tales with me.

Jonny says being able to through-skate is a huge privilege.

“Exploration like this isn’t accessible to most of the world. When people see my story, I’d like them to feel like they’re not alone. I am a pretty average person, and I carry joy and sadness with me like everyone else.”

“As long as you can acknowledge this and carry yourself with humility and respect, I would like people to feel like they can pursue whatever fulfils them without having to worry about judgment or logic. We have very, very little time here and very little time left – if you yearn for adventure, make it happen.”